Between Vienna and Shanghai

Jan 28, 2021 | JMW News

“What you wouldn’t see otherwise”, was the title of a blog article last March pointing out objects in the exhibition about the Ephrussi family that our visitors could not see due to the closure of the museums. Since direct exchange during guided tours was not possible at the time, a communication channel had to be found that made sense and ideally also provided added value. In this text, objects that usually did not have or had not yet had their say in the guided tours were given a voice.

In the meantime, the museums are still closed or have already been shuttered again; the Ephrussi family has long since made room for the “Shanghailänder” (“Shanghighlanders”) and the “Little Vienna in Shanghai” exhibition, highlighting the stories of those who had managed to reach the safe haven of Shanghai since 1938. In conversation with the curators in preparation for the exhibition, there was always talk of the many loans that had been made available by Viennese families. The numbers fluctuated between 800 and 900 items. Cultural educators should love objects and be happy about as many as possible. At the same time, the increasingly difficult task of making a selection has to be handled with even more care, because nobody can see everything in an exhibition. And I would add that you shouldn’t see everything at once, but rather come back a second time.

In this exhibition, the choice of objects that appear as narrators should best be made by our guests. “I spy with my little eye…” could only focus on one object in each room. The popular children’s game against boredom has personally served me wonderfully in many exhibitions and has enormously sharpened my view of small things and their stories. In this article I would like to introduce you to the married couple Ernst and Edith Grauaug.

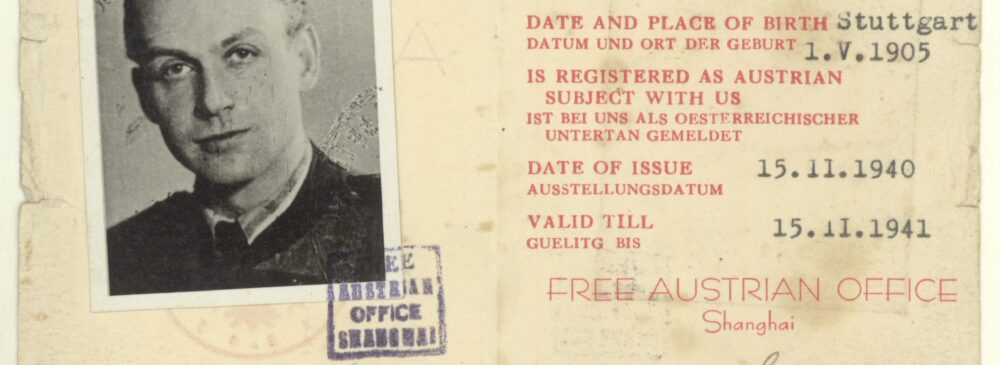

Image © JMW

The Free Austrian Office was an association founded in the 1940s to support Austrian refugees. The ID cards did not entitle anyone to anything, but were supposed to give their holders a sense of belonging. The founder of this Free Austrian Office must have been a monarchist, since the peculiar-looking eagle wears a crown and a laurel wreath. Members were not members, but rather Austrian “subjects.” How did Ernst Grauaug, whose ID card can be seen in the exhibition, feel about that?

Image © JMW

His wife Edith, who accompanied him into exile in China, acquired these dolls in Shanghai – whether she bought them or received them as a gift can no longer be determined. The former theater director worked as a pianist in a bar in Shanghai, Edith as a singer. Here she met an American, whom she followed to his homeland. Ernst stayed alone in Shanghai until he returned to Vienna and was able to stay afloat with a job at the American embassy.

Image © JMW

The Grauaugs had probably bought the ivory chopsticks for their joint household or received them as gifts. The object also keeps this detail to itself. What thoughts were going through Ernst Grauaug’s head when he packed them in Shanghai and unpacked them again in Vienna is also not known. In 2014, a friend of his second wife gave the Jewish Museum Vienna a gift consisting of photos of and documents on Edith and Ernst Grauaug and his parents. To be honest, entering “chopsticks” as a search term in the museum’s inventory would not have crossed my mind for a long time without this exhibition.

Image © JMW

Edith Grauaug greets the exhibition audience from a rickshaw. She’s smiling at us from the poster and it seems like she’s telling us. “Come closer and take a look around.” She is in a good mood, has just had her hair done and is probably wearing make-up. Her stage name in Shanghai was “Beer Barrel Songbird.” When she wasn’t singing, she poured out beer. The photo expresses self-confidence.

Image © JMW

The donation includes a bundle of photos showing Ernst Grauaug’s parents, who are not featured in the exhibition. Ernst’s father, the Vienna native Ludwig Grauaug, was the director of a theater in Stuttgart. You can see him sitting at a desk in this shot from January 1933, possibly in his office. His wife, Ida Sykora, Ernst’s mother, was an opera singer and can be seen in a photo on a balcony in Arosa, perhaps in a hotel? On the back she had written “Meinem Burschi” (“To my little boy” and “Mama” – on September 8, 1928.

Image © JMW

Often the gaps torn through history do not close, even when people leave their memories in the form of objects, photos or archival material to a museum. Visitors come across these gaps, which are sometimes larger and sometimes smaller, in the permanent exhibition “Our City! Jewish Vienna – Then to Now,” as well as in the temporary exhibitions of the Jewish Museum Vienna. This has often been discussed in workshops with school pupils; the young people usually accept the fact that there is a lack of knowledge and information. A good and wise comment on this was that the object on display definitely has a story, even if the people in the museum could not find it out.

Image © JMW

Cover image © JMW