“The past casts a heavy shadow on my heart”

Jan 3, 2017 | JMW News

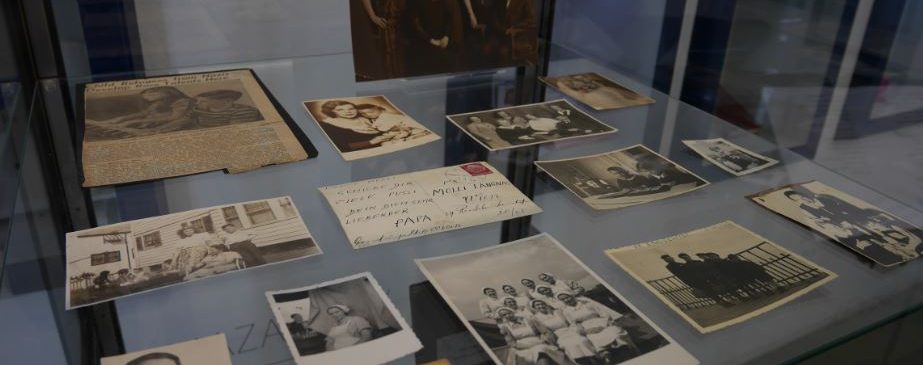

This summer has been anything but uneventful for us all. To our great delight, the Jewish Museum received a very special donation: documentation of an extraordinary life story, which—like many other Viennese Jewish family chronicles—began in Galicia. Because of the caesura of the Shoah, however, it became an important and exceptional testimony to daily Jewish life during World War II. It is the archive of Mignon Langnas, a highly interesting personage.

Mignon was born in Boryslaw/Boryslav (now in western Ukraine) in 1903 to Moses Rottenberg and Charlotte Schleifer. The pious family fled to Vienna in 1914 to escape from the pogroms and lived in Blumauergasse in the 2nd district. Mignon was eleven years old. Fourteen years later she married Leo Langnas from Lemberg/Lviv in the Polish Shul at Leopoldgasse14. They soon had a daughter, Erika, who died at the age of three, a dramatic event that Mignon never got over. She regarded the birth of her daughter Manuela, called Mollychen, and then Georg, or Georgerl, as a gift from heaven. She was constantly worried about the health of her children. The happy family life did not last long. After the annexation of Austria to Nazi Germany, Leo Langnas managed to escape to the USA but Mignon didn’t want to leave her aged parents in Vienna and sent the six-year old Manuela and four-year-old Georg alone on the ship to New York. Frances Weinstein, a relative, described their arrival as follows:

“My dear Aunt and Uncle and Cousin Mignon,

Yesterday I received your letters the very same day that your dear little children arrived in this country. I can very well understand what a terrible wrench it was for you to have to part with them, and it saddens me to think of you in pain, but then we were very happy to receive your precious jewels. I cannot tell you how very much surprised we were to see how lovely they are. Nelly and I went to the pier to receive the children, and there were many children on the boat, but I can truly say that Manuela and Georg were by far the most beautiful. Molly, with her golden braids tied with pink ribbons, her shining blue eyes and pink cheeks, looked like a ray of sunshine, and the dear little Georg, with his bright dark eyes and red cheeks and happy smile, also looked the picture of health. And a few minutes after I met him, he told Molli that he could talk a better English than I can German. Both children are adorable, we love them very much. We only beg you not to worry about them, for all of us will do the best and most practical things for the children. […] I only pray that you keep your strength and courage and God will grant the day to come soon when you will all be together and happy again.”

What followed was “a long journey of bitter tears,” as Mignon describes it. She was devoured with longing for her husband and children, as her letters reveal. But she didn’t dare abandon her parents to a certain death. To save them and herself, she trained as a nurse for the Jews remaining in Vienna and helped many people, particularly children, including the newborn Robert Schindel, today a major Austrian writer. She kept a diary throughout and wrote tirelessly to her loved ones in New York.

“At first I was almost crazed with pain, when two children’s arms embraced me and a sweet voice asked: ‘Are you my mom?’ But later I trained myself to be able to serve all these sick children and to be a ‘mom’ to them. I don’t want to work anywhere else but here. As you can see, my dearest ones, we are leading a quiet life, full of work and hope for a happy reunion with you.”

Mignon survived the Nazi regime and World War II in Vienna, and finally, marked by illness, managed to travel to her family in the USA in 1946. Her enjoyment of family life was short-lived, however. She died in 1949 as a result of the exhausting effort to save her Jewish patients, full of disquiet and doubts as to whether she had done the right thing to allow her husband and children to travel alone to freedom. “The past casts a heavy shadow on my heart,” she wrote shortly after her arrival in New York. And the diary entries a few weeks before her death can only hint at the dark memories that she must have been carrying with her.

“It was two months of inner struggle and unease. I cried frequently and was very distressed. Only I know the reasons and this tortures me. One day a swore to myself that I would pull myself together and at least ensure that my nearest and dearest did not have to suffer…”

Thanks to Elisabeth Fraller, who turned Mignon Langnas’s archive into a book, I became acquainted with George Langnas. After numerous discussions, Manuela and George decided to donate their mother’s archive to the Jewish Museum Vienna. We are exhibiting some of it in the Visual Display as a demonstration of our gratitude for this inestimable testimony of the most difficult time in the history of the Jews of Vienna.

Mignon’s intellectual legacy has now found a final home. It is to be hoped that she herself has also found peace.

The family of Mignon Langnas with director Danielle Spera

(c) JMW / Sonja Bachmayer

Cover photo: (c) JMW / Fuchs